Development: DNA & Detection Dogs

DNA

DNA to indicate relationships, movements etc.

If we are to eradicate American mink we will need to use every scrap of information about these animals that might be available. We will have to understand how far they travel, and when they travel. We will need to know about their breeding biology and behaviour, how large are their territories and where they live at different times of year. One of the most powerful tools for providing answers to these questions is in every cell of every American mink – their genetic identity, their DNA. By taking a few cells from a mink, we can potentially identify its parents and siblings, learn where it was born and find out where it has been. This is forensic science being put to use in the service of nature conservation.

To build the reference collection that will allow us to interpret American mink DNA, we routinely take a small piece of tissue from every animal caught, and every mink found dead on a road. These samples will allow us to build up a picture of the genetic diversity of mink across our region, and to look for patterns. For example, if we were to find that the American mink in north Norfolk were genetically no different from those in south Essex or west Cambridgeshire, we would infer that there is a great deal of mixing in the population. But if there are clusters of mink with different DNA profiles within our region, we could be sure that there is little or no mixing. If we take the DNA of a territorial adult female in coastal Suffolk, and then find that young animals captured in Norwich or Hatfield are her offspring, this helps us understand how far juveniles disperse from their natal area. Knowing this degree of dispersal is vital, for example, for us to plan a trapping regime that will keep our project Core Area (essentially Norfolk and Suffolk) free of immigrating American mink, or at least recognise immigration when it has occurred.

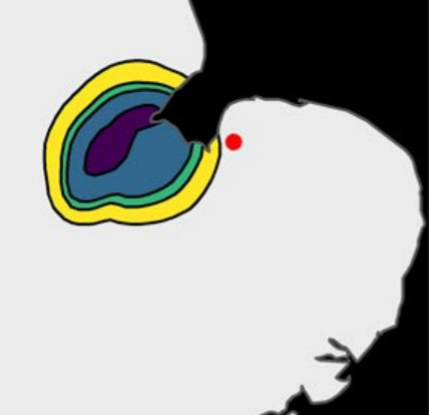

The genetic samples taken to date, and analysed by Professor Amos at Cambridge University, have enabled a ‘genetic map’ to be created that indicates where a mink is likely to have been born. This can help us answer questions like, ‘where on earth did that one come from!’; have we missed it previously or is it an immigrant? One such was a female caught rather unexpectedly on the Babingley on 1 April 2022. They indicate that this animal was probably born in the western corner of the Wash, probably in the River Welland catchment, and in all probability moved round the Wash until she reached the mouth of the Great Ouse, then into the Babingley and finally into one of our traps.

The Papers section gives examples of how studying mink DNA can help better understand American mink populations.

eDNA

eDNA to help us detect American mink at low densities

When American mink have been almost, but not quite, removed, finding the whereabouts of the last animals will be a major undertaking. We now believe that trapping alone, if sufficiently comprehensive, may be able to remove all mink. If not every one, then trapping should be able to reduce them to such a low density that females do not breed, which will inevitably lead to eradication. A suite of techniques are potentially available to find animals at low density, including trained mink dogs (see below), but all are labour intensive and focus on individual animals. It would save a huge amount of money and time if we had a way to be able to say that a particular river or lake is currently free of mink, so we can focus scarce resources on places where mink still remain.

Until very recently, there seemed no prospect of having a way to make such a determination, but advances in the sensitivity of molecular testing now offer just such a possibility for the future. Remarkably, geneticists can now detect the presence of a few cells of an organism in water samples. Science fiction has been turned into science fact, as it has now become almost routine to collect a litre of water from a river and be able to say whether otters, crayfish, tench, water hyacinth or indeed mink live upstream of the collection point. Cells are put into the water when an animal swims, urinates or defaecates in it. Much research work is required to turn this remarkable discovery into an effective tool for us, though. For example, if American mink cells are found, does this mean the animal(s) were present yesterday, within the past month, or within the past year? Can we say how many animals are present, or how far away they are? If no mink cells are present in one sample, do we need to repeat the sampling and testing to be sure the species is absent? So many questions, and as yet not many answers. This field of science, known as environmental (e)DNA, is developing rapidly but it may be some years before it is a tool that we can use at a wide geographical scale for mink.

Detection Dogs

Mink Dogs to help us find the last few American mink

Although the vast majority of American mink can be removed by trapping, in each area there may well be a few that take some time to trap. These animals are of no real concern when the objective is to simply reduce mink numbers in order to reduce their impact on native wildlife, but they represent the difference between success and failure for an eradication campaign such as the eradication trial being carried out by Waterlife Recovery East.

There are several ways in which American mink may be detected (e.g., sightings by the public, using camera traps, clay pads on rafts or environmental DNA), but all of these techniques suffer from the weakness of telling us where mink were – not necessarily where they are now. By far the best tool for locating mink in real time is a damp nose on the front of a well-trained dog. The qualities that make dogs so good at detecting drugs at airports, or tracking fleeing burglars for the police, are what make them so good at finding the slightest whiff of a mink and leading their handler to where the animal is hiding. Once located, usually in a burrow, traps can be set to catch the animal. Dogs are never used to attack or kill an American mink.

Dogs trained to look for any last surviving pest animals in an eradication project, be they mink, rats or pigs, are known as conservation dogs. New Zealanders lead the world in training dogs specifically for this purpose, but conservation dogs are increasingly helping pest eradication projects all over the world, and one (River) is already under training to become a mink dog in Norfolk. One of the main uses of trained dogs for mink is to follow up reports of sightings, where they can help determine if a mink really was there, or whether the report was more likely to have been a genuine case of mistaken identity.